Legal Status

None

Key Identification Features

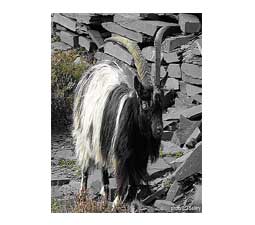

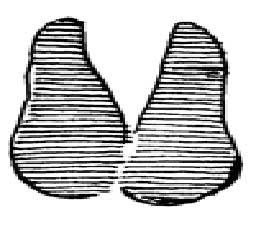

Feral goats are ruminants closely related to sheep, cattle and antelope of the Bovidae family. There is considerable variation in their coat colours and patterns due to regular breeding with escaped domesticated individuals over the years. Generally coats are white, grey, brown or black in colour with different patterns and shades. During winter and spring the males known as billies will develop a long shaggy mane. Both males and females known as nannies have a beard under the chin with male beards being more pronounced. Males and females grow horns throughout their lives which slow in winter leaving a growth ring for each year which can help to determine the age of an individual. Males develop considerably larger horns which can reach up to half a meter in length. Individuals which have descended from more recent domestic escapees will have horns which are set further apart and have a coiled shape. Descendants from older herds will have horns in a more swept back shape. The size of an adult feral goat will vary depending on the population’s origin and the habitat they occupy with males being larger than females. Males average 50 to 75kg and stand up to 60cm at the shoulder. Females weigh on average between 35 to 60kg and stand at 50cm to the shoulder. Feral goat’s tails are long and flat which are hairless on the underside.They have developed a distinctive thick pad of skin on the knees of the front legs and their hooves have a central spongy pad which allows for agile climbing. Hoof prints average 6cm long and 5cm wide which tend to splay. They are similar in shape to sheep tracks but appear more curved and evenly rounded.

Habitat

Feral goats can access areas which are unsuitable for other large herbivores in Ireland. Due to their flexible foot design they can access upland slopes which even sheep cannot reach. They are present in many upland habitats including mountains, coastal cliffs, scree slopes and on offshore islands. They can survive in remote areas at altitudes above two hundred meters. They require habitats with access to vegetation in areas with well-drained soil. They cannot tolerate periods of strong winds or heavy rain so they require access to sheltered woodlands or in coastal areas where trees are scarce they will shelter among boulders or inside caves. Goat herds will occupy traditional home ranges rarely traveling far from such territories throughout the year.

Food and Feeding Habits

Feral goats can be described as selective feeders preferring to browse rather than graze as other ruminants tend to do. They will eat a wide variety of food depending on the time of year. In summer their diet will mainly consist of grasses, sedges, rushes and bilberries. In winter they will switch to heather, gorse and shrubs. They will also strip bark from the trunks of oak, willow, spruce and pine tree species. In coastal areas they will eat seaweed. Feral goats will feed throughout the day in open areas in between periods spent ruminating among cover. In spring longer feeding periods are required as food is scarce and of poorer nutritional quality. Feral goats will form groups depending on their sex. Female herds containing under twelve individuals led by one dominant nanny is the only permanent social group in wild goat populations, such groups are composed of female relatives, their daughters and infant male kids under one years old. These groups will occupy small home ranges which can overlap with the territories of other female groups which sometimes allows for the mixing of members. During periods of food shortages large temporary groups of up to one hundred individuals may form to graze. Male goats spend their time in separate small groups for most of the year before joining a female herd for the rutting season.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The rutting season for feral goats is long, starting in August and running until December with a peak of mating activity occurring in October and November. During the rut male goats become more aggressive and territorial. At this time the billies will develop a strong musty odour which is produced by glands located behind the horns, near the tail and between the toes. This is added to by spraying urine on themselves to further increase the strength of the scent. Bellies will indulge in ritualized threats towards other males which include staring matches, beard shaking and horn lowering. Fights involving males of similar size are common and can go on for hours consisting of opponents rearing up on their hind legs before crashing their heads together. The mating strategy of billies involves following a nanny closely who is reaching the peak of her estrogen cycle for several days to thwart other males in the area and to establish his dominance. Courtship involves vocal, scent and visual signaling which will lead to mating. If a nanny fails to become pregnant after mating early in the rut she will try again at 20-day intervals for the remainder of the season until successful. Once pregnant gestation lasts for five months with usually one kid but occasionally twins being born in February to April. Newborn kids will average a birth weight of between 1.5 to 2.5kg. In their first week kids will remain hidden within vegetation or among rock cover remaining motionless for long periods, this is a survival strategy which was developed to counter the activity of predators at this vital time of the year. After they have gained sufficient strength they will join their mothers in the female herd. Kids are then weaned until they are six months old. Female kids will remain with the herd for life using the same territory while males will leave the group when they reach one year of age to join a male group. Female goats reach sexual maturity quite early being able to breed at only nine months of age. If kids can survive their first year which can see a high death rate due to their early season births which can be badly effected by a harsh spring they will on average reach 8 years of age with infant mortality rates higher for males than for females.

Current Distribution

Goats were one of the first animal species to be domesticated by humans and can be traced back to the Middle East and Asia 9,000 years ago. They spread with the movement of human rural populations and are now widespread on all inhabited continents. More recent introductions have established large populations in Australia, New Zealand, Africa and Hawaii. They arrived in Ireland around 4,000 years ago with Neolithic settlers. The later arrival of Vikings and the Normans increased the Irish numbers of goats as they were held in high regard by these societies. Goat numbers here reached a peak by the 19th century as over 240,000 were exported to England in 1926 alone. As this trade declined increased numbers of goats escaped or were purposefully released, a further decline in farmed goat numbers occurred with the increase in sheep rearing which was more economical and as major movements of rural populations to cities grew. For a brief period during the Second World War the numbers of wild goats fell dramatically as they were over hunted for their meat which was again exported to England. Ancient feral goat populations have been present since Neolithic times due to the goat’s tendency to revert to a wild state easily. Escapes and releases since then have continually added to those original populations.A large population is currently located in the Burren as they are well adapted to such an environment their density here can reach 14 individuals per km2. The current feral goat herds are present in most counties except for areas in eastern Connaught, southern Ulster and parts of the midlands. Their current number in Ireland could be under 5000 individuals.

Conservation Issues

If found in high enough concentrations locally feral goats can cause damage to commercial forestry by bark stripping, eating tree leaves and young leader shoots. In farming areas they can knock over stonewalls and ruin new grasslands set aside for sheep. They can be of benefit in some areas as a conservational grazing tool which stops the development of birch, hazel and willow species in rich grassland habitats. They also have a value for tourism and recreational watching opportunities in isolated rural locations. There may not be any ancient herds remaining due to recently released domestic goats so protection from such cross breeding is needed to retain their genetic heritage which requires the active culling of recent arrivals of more modern breeds. Feral goats are not a species whose spread will have a negative impact on any of our three deer species as they do not compete directly for the same food types and they tend to range in different habitat locations. The re-introduction of the golden eagle to Ireland may yet see some effect on the feral goat in some areas particularly in Donegal as these birds are a natural predator of the goat.Currently most deaths of young feral goats occur naturally due largely to their unusually early birth time in early spring which can result in exposure deaths of kids when harsh weather conditions occur. Feral goats are not a legally protected species and can be culled in most areas generally by farmers. This is the main method of population control but it should be carried out in an organized way nationally so as over culling does not occur. Feral goat herds found within national parks are actively conserved and managed.